Simply put, the European legislator decided upon promulgating a regulation that obliges future virtual asset providers to broadcast personal data for all transactions along in the international value chain for reasons of preventing money laundering and terrorist finance.

What personal data is involved?

Well, first of all, the fact that you as a customer (or receiver) own virtual assets (a fact that, see the ledger hack, has proven to be very private and sensitive information). It regards the following information about the sender/originator:(a) the name of the originator;

(b) the originator’s distributed ledger address, in cases where a transfer of crypto-assets is registered on a network using DLT or similar technology, and the crypto-asset account number of the originator, where such an account exists and is used to process the transaction;

(c) the originator’s crypto-asset account number, in cases where a transfer of crypto-assets is not registered on a network using DLT or similar technology;

(d) the originator’s address, including the name of the country, official personal document number and customer identification number, or, alternatively, the originator’s date and place of birth; and

(e) subject to the existence of the necessary field in the relevant message format, and where provided by the originator to its crypto-asset service provider, the current LEI or, in its absence, any other available equivalent official identifier of the originator.

And it also covers data of the person/entity that you are sending information to:

(a) the name of the beneficiary,

(b) the beneficiary’s distributed ledger address, in cases where a transfer of crypto-assets is registered on a network using DLT or similar technology, and the beneficiary’s crypto-asset account number, where such an account exists and is used to process the transaction;

(c) the beneficiary’s crypto-asset account number, in cases where a transfer of crypto-assets is not registered on a network using DLT or similar technology; and

(d) subject to the existence of the necessary field in the relevant message format, and where provided by the originator to its crypto-asset service provider, the current LEI or, in its absence, any other available equivalent official identifier of the beneficiary.

Article 24Provision of informationPayment service providers and crypto-asset service providers shall respond fully and without delay, including by means of a central contact point in accordance with Article 45(9) of Directive (EU) 2015/849, where such a contact point has been appointed, and in accordance with the procedural requirements laid down in the national law of the Member State in which they are established or have their registered office, as applicable, to enquiries exclusively from the authorities responsible for preventing and combating money laundering or terrorist financing of that Member State concerning the information required under this Regulation.

Pursuant to Article 52 of the Charter, any limitation on the exercise of the rights and freedoms recognised by this Charter must be provided for by law and respect the essence of those rights and freedoms. Subject to the principle of proportionality, limitations may be made only if they are necessary and genuinely meet objectives of general interest recognised by the Union or the need to protect the rights and freedoms of others7 . This means that legislative measures that limit the right to privacy and data protection have to be specific in order to correspond to objectives of general interest pursued and should not constitute disproportionate and unreasonable interference undermining the substance of those rights.

Hey, is that also third party privacy issue popping up?

Yes indeed. This regulation is not only an infringement to customers of VASPs, but to all receivers of virtual asset transfers from the European Union. Those recipients will be unable to know where and which data on them has been submitted, stored and retained by the sending VASP as they have no legal relation with that entity. Yet the sending VASP processes their personal information and distributes it regardless of the existence of any provable relation to money laundering or terrorist finance.

The consequence of this construct is similar as that for the Second Payment Services Directive and the European Data Protection Board has in 2020 stipulated in its guideline that for these uninvolved third party data, called 'silent party' data, controllers need to take serious precautions.

In this respect, the controller (AISP or PISP) has to establish the necessary safeguards for the processing in order to protect the rights of data subjects. This includes technical measures to ensure that silent party data are not processed for a purpose other than the purpose for which the personal data were originally collected by PISPs and AISPs. If feasible, also encryption or other techniques should be applied to achieve an appropriate level of security and data minimisation.

Also the EDPB outlines that no other processing of data is allowed outside the scope of the regulation:

With regard to further processing of silent party data on the basis of legitimate interest, the EDPB is of the opinion that these data cannot be used for a purpose other than that for which the personal data have been collected, other on the basis of EU or Member State law.

How about the international data transfer and privacy issues?

Yes, good point. The regulation is a one size fits all for crypto-transfers, whereas for fiat-transactions differences are made between in EU and EU/non-EU countries. This leads to the question how non EU countries deal with data that EU companies are forced to distribute all over the world.

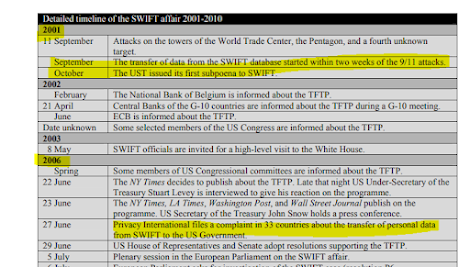

In the immediate post 9/11 political discussion in Europe it became clear that European citizens and politicians were being cheated upon by the US government (that was harvesting EU data immediately after the 9/11 attack). A range of measures, discussions etc followed after the illegal snooping of the US on EU customer data was found out. This is also described by Mara Wesseling. In today's terms we can see a repeat of the topic during the Max Schrems discussions on Facebook data, which also has a serious bearing on financial transactions and financial transaction information exchange.

In essence, those discussions on legitimacy and data protection for international data transfer have not really been resolved. And the current EU regulation does not change it, as it obliges companies to distribute data to entities without proper assurance that the receiving companies/countries protect the data of customers sufficiently. Which means that all VASPs that fully follow this regulation can be held liable by data protection supervisors or citizens that face damages from data breaches and insufficient data protection measures of those VASPs.

So why still this requirement, does it work in practice?

Well, all law enforcers/governments in essence just land grab each tool in the toolbox to claim it is useful. And for this regulation they say: 'this is an obligation for banks too, so crypto must follow'. However, the bank regulation is in operation for almost 2 decades now and no formal evaluations of the effectivity and usefulness have been done.

The fact that other players have the same obligation does not mean it is therefore suddenly proportional. Rather, it is disproportional to the other players as well, but those are unwilling to challenge the rule as over the years they are being fined into submission.

Where does this idea/requirement come from?

Way back from 1995 onwards, the world was less digital and we had little big data floating all around the world. Intelligence and law enforcement community were however keen to introduce far reaching KYC and data transfer requirements. The first efforts in the US were unsuccessful but the 9/11 attacks completely changed the momentum, as documented by Mara Wesseling in her dissertation:

The attacks of 11 September 2001 substantially changed the urgency and importance assigned to these different debates. The relative insignificance of the amounts of money involved in terrorism, the burden on the financial sector, the civil liberties implications of strengthened regulation, and the doubts about the use of UN economic sanctions, all became subordinate to the increased urgency of terrorism (p.90-91).

The story for financial institutions after 9/11/2001 was simple. A whole bunch of intrusive regulations were forced upon them with the following explanation: "If we need to get to a terrorist, we need to be aware of their transactions fast en early and the current structure of paperwork and international law enforcement is too complex and timely. So rather than file proper paperwork based on due diligence we request financial institutions to broadcast the data all over the world so any local police officer can investigate the two legs of a financial transaction by requesting access to the transaction data at the local end."

Politically banks couldn't resist cooperating for fear of being branded cooperative with terrorists. And mind you, the terrorist approach was in essence an upgrade of previous efforts to get banks on board to do KYC to prevent money laundering. But that political frame got a bit outdated so the 9/11 attacks were a welcome present to the law enforcement/intelligence community as a momentum to change the scenery in a fundamental way.

What is the risk of this regulation?

In essence, the broadcasting requirement as it was implemented after 9/11 in banking, was a shortcut for local law enforcement (or other national security offices) that would provide easy access to EU data in the US for example. And make no mistake: local governments weren't waiting for the law to be in place, they just got what they wanted and started downloading swift transactions within 2 weeks of the 9/11 attack. This became known only five years later, Wesseling explains:

The main risk involved in this data harvesting/broadcasting regulation is that it is used for other purposes in a way that is not specifically and officially set out in law. The application of the rule would then lead to data processing of citizens data without legal title. And it is exactly this challenge that one Dutch VASP, Bitonic, faced in 2020. Either violate the AVG or AML-laws.

Bitonic succeeded in challenging supervisors requirements related to this rule and then deleted all customer data that were unduly harvested/collected. But in order to remain in business and keep their license to operate they were first of all forced by financial supervisors to consciously violate the AVG. But close readers of the regulation will now understand what is meant with the article 23. Supervisors will use this regulation to force payment service providers and crypto-asset service providers to restrict transfers of assets that are not to the liking of the supervisor and that are beyond the scope of the regulation itself.

23. Payment service providers and crypto-asset service providers shall have in place internal policies, procedures and controls to ensure the implementation of Union and national restrictive measures when performing transfers of funds and crypto-assets under this Regulation.

Rather than waiting for these constitutional accidents to happen again during the licensing process for Mica-r, the market players may wish to address them in advance to ensure legal clarity and compatibility with fundamental rights.